India’s delivery ecosystem has transformed dramatically over the past decade. What began as restaurant delivery and scheduled grocery e-commerce has evolved into a competitive, fast-growing landscape encompassing instant commerce, bulk grocery delivery, and B2B supply chain platforms. In 2025, quick commerce and online food delivery have become habitual for urban consumers, while the B2B backend is still stabilizing.

📈 Historical Evolution

Food delivery took off around 2015, with Swiggy and Zomato emerging as the dominant players. Earlier competitors like Foodpanda and Uber Eats exited or were acquired. Grocery delivery experienced early failures in 2016–17 but recovered through companies like BigBasket and Grofers (now Blinkit). The COVID-19 pandemic catalyzed mass adoption across both segments.

Quick commerce (10–30 minute delivery) emerged around 2021–22, led by Blinkit’s rebranding and the arrival of Zepto, sparking a new wave of VC funding and dark store expansion. Meanwhile, the B2B space saw growth through players like Udaan, Jumbotail, and Ninjacart, but has since seen consolidation due to tight margins.

🏢 Major Players

Quick Commerce (B2C):

- Blinkit (acquired by Zomato): Market leader with ~46% share.

- Zepto: Startup sensation with ~29% share, focused on metros.

- Swiggy Instamart: 25% share, integrated with Swiggy app.

- BigBasket Now, Dunzo: Niche players, limited geography or scale.

Scheduled Grocery (B2C):

- BigBasket (Tata): Full-stack inventory-led model; strong in staples.

- JioMart (Reliance): Deep reach, value-driven.

- Amazon Fresh, Flipkart Supermart: Scheduled slots, limited presence.

- Milkbasket/BB Daily: Micro-delivery subscription models.

Food Delivery (B2C):

- Zomato: ~58% market share; dominant in food and quick commerce.

- Swiggy: ~42% share; broader service portfolio (including Genie, Instamart).

- Domino’s: Largest single-brand QSR player with own delivery fleet.

- Others like Uber Eats and Amazon Food have exited the space.

B2B Grocery Supply:

- Udaan: Wholesale marketplace connecting brands with retailers.

- Jumbotail: Focus on kirana digitization and supply.

- Ninjacart: Farm-to-retail fresh produce delivery.

- Zomato Hyperpure: Restaurant ingredient supplies.

🔁 Business Models

India’s delivery economy spans several models:

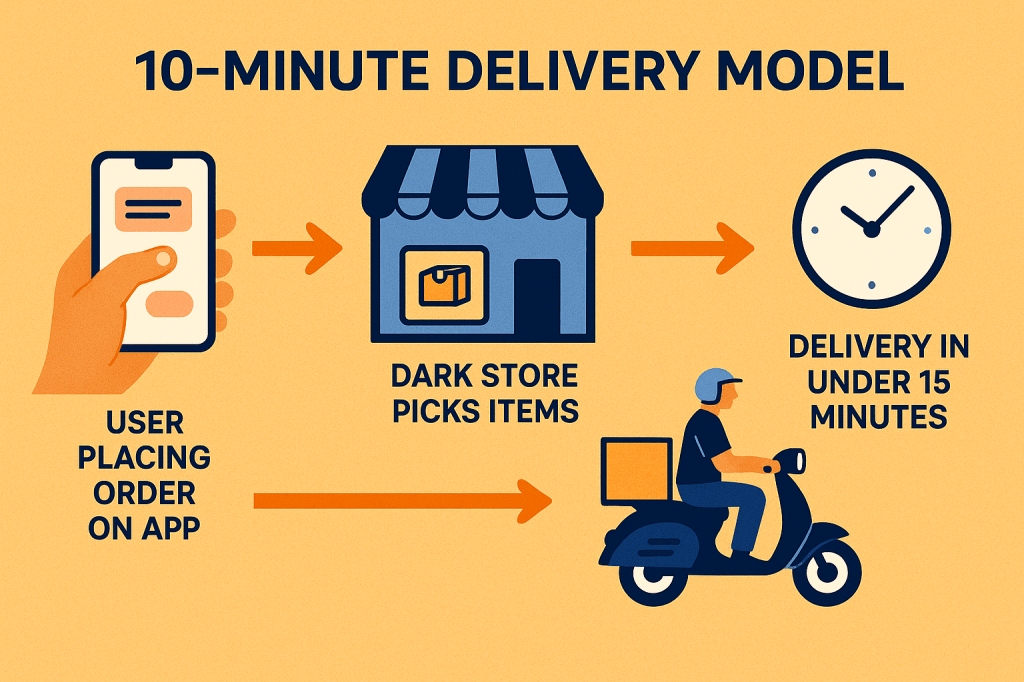

- 10-min Q-commerce (Blinkit, Zepto): Small baskets, dark stores, ultra-speed.

- Scheduled grocery (BigBasket): Full assortment, planned orders.

- Hyperlocal marketplace (Dunzo): Store-pick and delivery.

- Food delivery aggregators (Swiggy, Zomato): Restaurant marketplace + logistics.

- B2B wholesale (Udaan, Jumbotail): Bulk sales to kiranas, often credit-based.

- Cloud kitchens & private labels: Vertical integration for better margins.

- Subscription micro-delivery (BB Daily): Fixed daily essentials delivery.

These are converging – most major players now operate across 2–3 of these models.

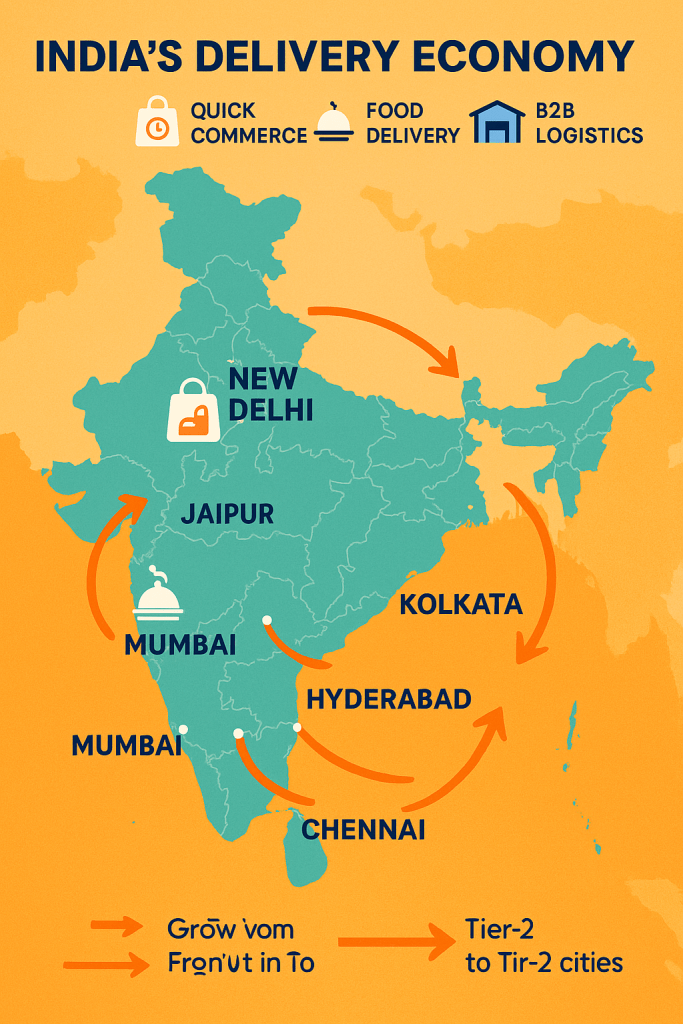

🌆 Key Cities and Regional Focus

- The top 8 metros — Delhi NCR, Mumbai, Bangalore, Hyderabad, Chennai, Pune, Kolkata, Ahmedabad — drive over 60% of order volume.

- Tier 2 cities are growing fast but have lower frequency and thinner margins.

- Rural markets remain largely untouched.

- Companies focus on densifying operations in top metros for profitability (e.g. adding more dark stores in Bengaluru vs. launching in new towns).

👥 Customer Segments

- Urban Millennials/Gen Z: Core base. Frequent users of both food and grocery apps. Comfort with impulse buying.

- Middle-Class Families: Use scheduled grocery delivery + quick commerce for top-ups. Cost-sensitive but loyal if reliable.

- B2B (Kirana stores, Restaurants): Purchase from Udaan, Jumbotail, or Hyperpure. Focus on pricing, reliability, and credit.

- Behavioral Trends:

- High frequency (e.g., Blinkit and Zepto see 3–5 orders/week per user).

- Gen Z is the fastest-growing segment.

- Shift toward premium/instant gratification purchases.

⚔️ Competitive Dynamics

- Zomato–Swiggy duopoly in food delivery; stable but competitive.

- Blinkit–Zepto–Instamart dominate quick commerce (~95% market).

- Consolidation: Zomato acquired Blinkit, Reliance invested in Dunzo, Tata owns BigBasket.

- ONDC, the government-backed open network, is emerging as a wildcard in food/grocery with lower commissions.

- Companies are shifting from growth-at-any-cost to unit economics and profitability:

- Blinkit became contribution margin positive in 2024.

- Swiggy targets profitability for Instamart by 2025.

- Food delivery profits fund grocery expansion.

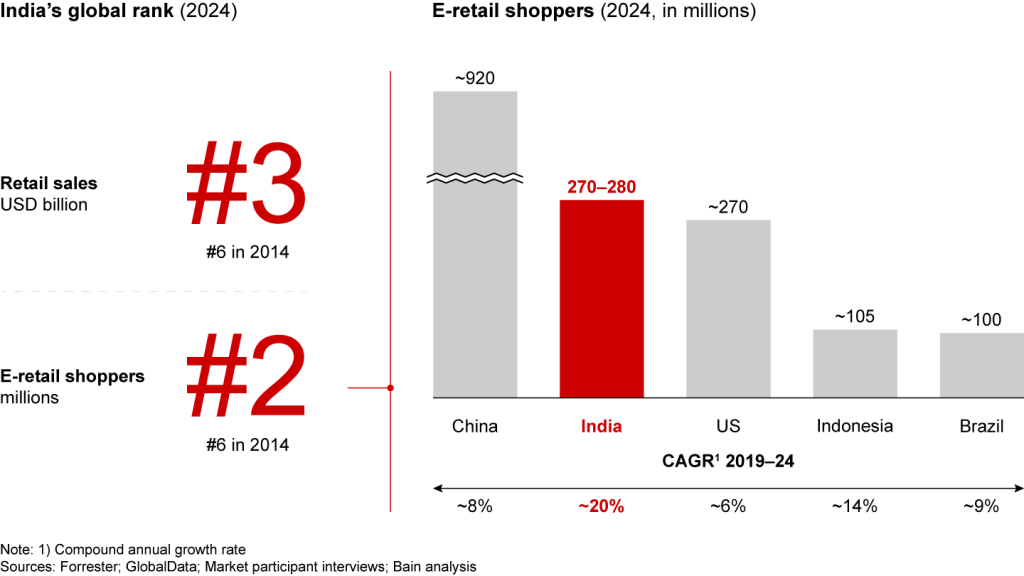

The Indian quick commerce (q-commerce) market, characterized by ultra-fast delivery (typically within 10–30 minutes), is experiencing explosive growth, fundamentally reshaping the country’s retail landscape.

Market Size and Growth

• The sector is currently valued at approximately $3.34 billion (2024) and is projected to reach between $5 billion and $5.38 billion by 2025, with forecasts extending to nearly $10 billion by 2029.

• Annual growth rates are among the highest in retail, with estimates ranging from 40% to 100% year-on-year, far outpacing traditional retail and standard e-commerce channels.

• Quick commerce already accounts for about half of all e-commerce grocery sales and nearly 7% of the total addressable market, indicating significant room for further expansion.

Key Trends

• Urban Focus, Expanding Reach: Initially concentrated in major metros, q-commerce is now rapidly expanding into tier-2 and smaller cities, driven by rising urbanization, smartphone penetration, and a young, tech-savvy consumer base.

• Beyond Groceries: While groceries and daily essentials remain core, platforms are diversifying into electronics, personal care, and premium categories to increase average order values and market share.

• Technology-Driven Efficiency: The sector leverages AI, data analytics, and micro-fulfillment centers (dark stores) to optimize inventory and delivery, enabling the promise of 10–30 minute fulfillment.

• Direct Sourcing and D2C Growth: Platforms increasingly partner directly with manufacturers and feature a growing mix of direct-to-consumer (D2C) and new-age brands, with over 30% of offerings on some platforms now D2C.

Major Players

• The market is dominated by Swiggy Instamart, Blinkit (Zomato), Zepto, BigBasket, and Dunzo, who collectively hold more than 80% market share.

• Traditional e-commerce giants like Amazon and Flipkart are entering the space, intensifying competition.

• User engagement is high: for example, Blinkit reported 8.8 million visits in Q1 2024.

Consumer Behavior

• The core user base consists of urban millennials and Gen Z, who prioritize convenience, speed, and digital payment options.

• The average order value is rising, with platforms pushing into higher-value categories to drive profitability.

• Consumer loyalty is driven by delivery speed, product quality, ease of use, and competitive pricing

Challenges

• Logistics and Infrastructure: India’s diverse geography and urban congestion present delivery challenges, though innovations like dark stores and AI-powered routing are mitigating these issues.

• Profitability and Consolidation: As competition intensifies, differentiation and operational efficiency are critical. The market may see consolidation, with a few dominant players emerging, similar to other Indian digital sectors.

• Consumer Trust: Ensuring product quality, data privacy, and consistent service is essential to maintain and grow the customer base.

Future Outlook

• Quick commerce is expected to continue its rapid expansion, fueled by further penetration into smaller cities, new product categories, and ongoing investment in technology and logistics.

• The sector’s unique strengths-speed, proximity, and convenience-position it to capture a substantial share of India’s $250 billion urban grocery market and beyond.

• By 2029, the user base is expected to nearly triple, reaching over 60 million, with average revenue per user also rising sharply.

Conclusion

Quick commerce is not just a fast-growing retail channel in India-it is redefining how Indian consumers shop, setting new standards for convenience and speed. The next phase will see deeper market penetration, broader product offerings, and likely consolidation as the sector matures and competition intensifies